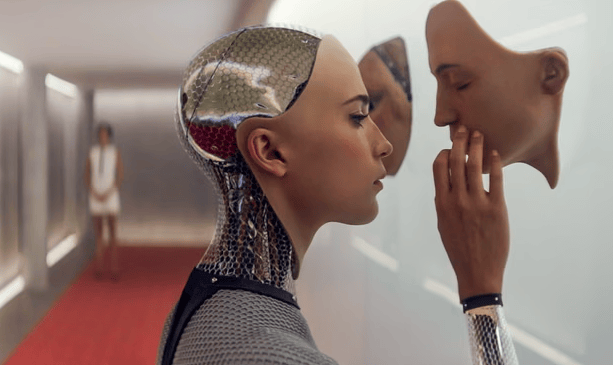

‘Ava’ from the 2014 Alex Garland film ExMachina. Credit: A24

Greetings, humans.

On a recent trip to San Francisco, I was struck by two things. One, the absolute glut of billboards trumpeting all the ways AI is going to transform our lives for the better. Two, the lack of basic infrastructure and social services needed to support the city’s human population.

In a city filled with self-driving taxis and apps for opening apartment doors, why haven’t we figured out how to make public transit accessible and housing affordable? Why did I have to go to three different pharmacies to get a basic prescription filled?

I’m increasingly convinced that the reason lies, in part, with the stories we are telling about technology—stories that celebrate individual creativity, capitalistic growth, traditional gender roles, and the subjugation of less intelligent (human) beings.

That’s why I’m thrilled to bring you an interview with Nina Beguš. Beguš is researcher and lecturer at UC Berkeley who spends a lot of time thinking about how fictional narratives are shaping AI—and wants us to pull our collective imaginations out of the sexy/killer robot trope and write some better stories.

It’s a long read, but one that goes well with a plate of leftover turkey and mashed potatoes, so dig in.

— Maddie

A literary scholar explains how ancient myths shape modern AI

There’s a story that’s been with us for thousands of years, told and retold across space and time. It goes something like this: A man carves a statue of the perfect woman, then falls in love with it. With a bit of divine intervention, this artificial being is brought to life.

Nina Beguš, a researcher at the University of California, Berkeley with a PhD in comparative literature, sees this narrative template—which in Western literature has roots in the ancient Greek myth of Pygmalion—popping up in a surprising place: Siri, ChatGPT, and the other so-called “AI” tools taking the world by storm. As Beguš argues in her new book Artificial Humanities: A Fictional Perspective on Language in AI, the Pygmalion myth is one of the main tropes technology developers fall back on when designing new AI systems. It’s a big reason these systems are so often feminine, submissive, syncophantic, and even sexy.

To Beguš, the power of fiction to shape emerging AI technology should not be dismissed. Rather, it calls for an entirely new field of study, the Artificial Humanities, which brings philosophers, literary scholars, historians, gender studies experts, and other humanists to the table of AI development. Without their participation, Beguš worries that the most obvious cultural memes, from ancient mythology to Hollywood science fiction—killer robots, sexy voice assistants, even the idea that humanity represents the pinnacle of intelligence—will limit our collective imagination of what AI can be. “In order to shed off the Pygmalionesque ballast we all implicitly foster, we need the humanities at the table,” Beguš writes.

The Science of Fiction spoke with Beguš about the new field of Artificial Humanities, the feedback loop between fiction and AI development, and how better stories can help us build more useful, ethical, and interesting machines.

The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Tell me about your academic background and how it came to intersect with AI?

Credit: Nina Beguš

When I was doing my masters in continental Europe, I saw all these breakthroughs happening in technology. It was ImageNet at the time, and Siri. And I was looking at those breakthroughs and reading literature and saying, ‘Wow, the overlap is so uncanny, what’s going on here?’

Now it might seem obvious to say “Yes, the influence between the world of fiction and the imaginary, the world of ideas, and the world of practice and technology building is definitely there, and it goes both ways.” But at that time, it wasn’t such a given. Especially since people tend to see fiction as not doing any real work in the actual world.

But this is so much not the case. And I think now with AI, that’s really obvious. It’s clear there’s this unprecedented power of fiction, especially in technological spaces, doing actual work on how we build AI and also how we relate to these products.

And so I was thinking about all these stories, and I framed it around the Pygmalion myth. Which is such a bizarre myth: you’re building something, then you fall in love with it, you start to take care of it and there’s this romantic, erotic aspect. It just seemed so bizarre, but so present.

And I looked into different mythologies and folk stories, and you find it everywhere. You find it in Europe, North Africa, on the Silk Road, in Native American folk stories. It’s such an archetypal myth. So in my book, I pretty much limited myself to the Pygmalion myth.

I think the first time that really struck me that something was going on was Siri. It was a woman—all of the early [voice] assistants were women. It had this subservient nature of a helpful assistant. It was trying to be a product that builds rapport with you.

Something that today, 15 years later, we still see with large language models and a lot of other products. We kind of can’t break out of this persona.

So you got an iPhone for the first time, and that’s when you came to this realization that this mythological tale is informing modern technology?

Yes. This is where I started noticing things.

Then the more I looked, the worse it got. Replika came to be very early—it was already 2015 when it started getting lots of users. It’s not how it started: the CEO of Replika wanted to cope with her grief and created a digital double chatbot of her deceased friend. Which people immediately started using it as a companion, as an AI boyfriend/girlfriend.

And so, seeing what the Silicon Valley people were saying about the films Ex Machina, and Her, that were very popular back then. Seeing them saying ‘this just affirms our trajectory of product development,’ I’m not surprised we are where we are today.

People tend to see fiction as not doing any real work. This is so much not the case.

There’s this companionship aspect that’s now being put into everything.

OpenAI has for years been making a clear claim they are inspired by the movie Her. They wanted to use Scarlett Johansson’s voice. She just went public with her refusal of it. In October, they announced they’re going to do more erotica features. It’s so Pygmalionesque.

Your book discusses a new field you’re calling Artificial Humanities. How did the idea for the Artificial Humanities first come to you? And why is now the right time for this field?

Two things. I started talking to engineers early on when I was writing my literary dissertation

and they themselves said they’re dealing with ethical questions in their daily work they’re not equipped to solve. It was a very clear call to us.

What was even more interesting: I realized we’re asking the same questions. Us humanities people and them, the very technical people. The very same questions, just trying to answer them from a different disciplinary background.

So very early on, my project got manifesto-y in nature. I said ‘The only way to do this well is not to put ethics on as a bandaid on the end of the product’—this was the idea back in the 2010s— ‘it’s too late then. You have to start at the very beginning. You have to put humanists at the table of creation where the product is being made.’ So I made this call that I framed as Artificial Humanities to include humanistic insights into development.

I came up with a new term because there was nothing explaining what I wanted to do. Digital humanities really didn’t cut it, or computational humanities. They were using computational methods and applying them to humanistic materials. I took humanistic insights for computing. So I came up with a new term that kinda explained what I’m trying to do.

But what really affirmed me in my trajectory was I finished my PhD and immediately got a job at this non-profit [the Berggruen Institute] where we had artists, thinkers and technologists working together. And what happened is, they [the technologists] need us so much, they started paying us for projects. And we turned into a for-profit and started doing philosophical consulting: coming into companies at different levels. Sometimes with engineering teams working on a specific problem, sometimes with the C suite working more on strategy. A big variety of projects, I’d say.

And they wanted to talk. It obviously was very much needed, this humanistic side, and they knew it. But business is business—you’re ultimately serving capitalism. Whereas in academia, you have time to focus deeply. You can focus on errors. You can focus on the process.

So I think it’s very important that both academics and the industry researchers keep pursuing research questions in AI, because they’re going to get very different results.

What do you see as the key questions you’d like the Artificial Humanities to tackle?

My main question was “why are we building AI as this human-like mind?”

Obviously, it goes all back to the history of AI, even with Alan Turing in the late 40s and 50s, before we got the term artificial intelligence. You can see him thinking about AI as a human-like mind. He brings fiction in. In this big paper on the Turing Test, that’s 1950, he talks about a foolproof way of discovering if you’re talking to a machine or a human. He says, just ask the machine to write you a sonnet, and it will say ‘I can’t possibly do that.’

Fiction is very much there. And the way he imagines AI as this child that has the potential to grow, that you can teach, right? A machine that learns.

It kinda stayed this way. Even technologists who came after Turing had this idea. The interface between human and machine was always language, mostly text. It was easier, and less giving away of the identity.

You have to put humanists at the table of creation where the product is being made

Basically what happened with neural nets is we got enough compute, and then it worked. So we didn’t really move much farther away than where we were in the 50s with the whole idea of what AI could be. And we still see that today, with this intense push toward human likeness.

So that’s one big question for me: how to get out of this?

I think it’s extremely difficult to imagine. Just looking at the fictional attempts to do it, I’ve only found one writer who consistently can. That’s Stanislaw Lem. He can imagine a machine in a non-human way. In Solaris, you have ocean-like intelligence. Gollem XIV is this supercomputer, it’s in no way like a human.

But just look at Hollywood. Look at the last 10 to 15 years in fiction: It’s always a human-like robot or a virtual assistant.

Ex Machina and Her are so known. In Her, you have this human-to-humanlike relationship between the man and a virtual assistant. But in the end, when she breaks up with him, she evolves. She’s in a different world and she has no vocabulary to explain where she is. So she uses the metaphor of a book; saying the words are just floating further and further apart.

Which I think tells us a lot. We keep using metaphors for computing. Even artificial intelligence is a metaphor. Machine as a human mind is a metaphor. So you can see the filmmaker really grappling with the idea of a machine that’s non-human and having a hard time presenting it.

So that’s Spike Jones. And Alex Garland, with Ex Machina, really wanted to show how the robot, Ava, is experiencing the world visually. He wanted to have a visual rendition. And failed. He said ‘I couldn’t use that in the film.’ It’s so hard to break out of it.

So that’s the first problem—we don’t have a lot of writers that can do this well.

The second one is that the engineering has changed. Machine learning is a whole new beast.

Fifteen years ago, when I talked to engineers, they’d say “I write a program, if there’s a surprising output in the machine, it’s an error. I know what the machine should produce.” That’s industrial engineering. It’s based around the human: you push a button, pull a lever, and get a result. It automates the human intention.

With machine learning, the engineering itself has changed so that when you create an architecture, like the transformers [editor’s note: transformers are the AI neural network architecture that have been adopted for training large language models], they just happen to work well on text because it’s sequential. You have to discover their capabilities. You have to see where the potential is and what the possibilities are. You don’t really know what you made.

So I think it’s a little disappointing seeing just us going in this human-like direction where the true potential of machines is beyond the human.

What do you see as the big tropes from fiction that are coloring the development of this technology today?

It’s very shallow. They [AI developers] cherry-pick what they think is useful.

Amit Singhal, who led Google search for a long time, has a PhD in information retrieval. He saw the Star Trek computer as the North Star in building Google search. When he left Google, he said “I believe I succeeded in building the Star Trek computer.”

Fiction isn’t just a direct influence or inspiration. It’s also a space to speculate on the idea, to try out different scenarios. And I see Silicon Valley using it a lot, in design or innovation, but also just reflection. A lot of them write and publish stories. Jack Clark, of Anthropic, writes a newsletter and adds a short story he wrote at the end of every newsletter, just thinking about the problems he could foresee, through fictional means.

The value of fiction is immense. You can share very intimate knowledge and presuppositions with people publicly. It’s both an intimate and public discourse where you can try out ideas.

So there’s that.

This other paper [I wrote] on experimental narratives really showed how our cultural imaginary is so prevalent in all of us. I tried people out—I gave them stories to write, and gave machines very general prompts, around the Pygmalion myth. I didn’t ask for the myth directly, because most people wouldn’t know what that was. But every single one of them delivered.

Pygmalion looking up at his statue. Credit: Wikipedia

They know the narrative template of the myth. They completely followed it. Which tells you a lot about how our cultural imaginary works. These narrative templates we all share and inherit are doing a lot of work for technologists.

There’s a subfield of AI called priming: it’s how you introduce your product that changes how people are going to use it. So if you say this is a manipulative AI, or a friendly AI, you’ll get completely different use cases.

I think what’s really happening now is we’re entering an era of narrative economics. The way you shape a story about a product is everything.

How do these narrative templates affect, or inflate, our understanding of what AI chatbots really are capable of? They use first person pronouns. They use emotional language. Are tech companies priming us to think there is a person behind these products?

Yes. They are.

The current industry standard is “I am not a human,” but then, it relates to you as a human. So they’re kind of walking this line.

What I think is really happening: we have a new kind of relation in the world, and that’s with machines that learn. Whenever there is a big shift, people like to go back to what we know. So we go back to the human-to-human relation, because that’s all we know.

So this requires us to invent a new kind of relation. It will take time to figure out what these machines are. To figure out what we mean by the concepts we’re using—agency, creativity, all of what’s projected onto machines now.

I think these machines are just so prone to metaphors. That something is like another thing.

We’re really struggling with just mere vocabulary. We don’t have the words to describe this new reality quite yet.

Which is where fiction could really come in handy, especially science fiction.

In science fiction, you’re in this world. And there’s a vehicle that [the writer says is] a ship. And you know it’s not a ship. But the word serves as a placeholder to imagine this different world. You can accommodate this new idea.

So this placeholder power of fiction is something I think we could tap into as well.

In science fiction, we have this trope about the AI apocalypse. And we tech developers and experts taking this very seriously. We see AI researchers writing open letters about how we need to slow AI development, citing concerns that superintelligent AI could try to wipe humanity out. How much is this idea drawing on fiction—and is it a valid concern?

I’m wondering about this all the time. Here in Berkeley, there’s lots of AI risk people.

Obviously, we humans like stories. We like stories that are big—that can sell. So there’s one way this big story gives, not credit, but weight, to your invention.

If you think about Geoffrey Hinton, he really went into that warning phase [editor’s note: former Google engineer and ‘AI godfather] Geoffrey Hinton has recently warned that AI could wipe humanity out in the coming decades]. For him, it’s not to say “what I’ve invented is so big it’s gonna change the world”. There are some people thinking this way. I think you can see that in Sam Altman. But with some people, it’s also personal responsibility that comes with what you’ve created. Frankensteinian, in that way.

We’re entering an era of narrative economics. The way you shape a story about a product is everything.

So there’s that. But when I think about their assumptions, I think there’s one valid assumption that leads them toward AI risk. And that is that AI is not limited by biology.

If you look at information transmission and processing: computers are really good at it. We’re slow. It takes years to learn as a human. AI doesn’t have those limitations at all. So this kind of reasoning, I can see them taking that and landing at catastrophe.

It’s all stories. Even when you look at journalistic writing [on AI], pretty much everyone starts with a story we all know, that’s kind of fictional, just to get people the idea. Even when I read medical academic journals, they sometimes start with a fictional story. The more you look, the more surprised you are where you find fiction.

You write in your book that ‘In treating robots as subdued to our control, as paralyzed humans, and as romantic partners, we are constraining the robotic potential.’ How are our stories about AI constraining them? And how can we start breaking out of that and writing different stories?

Well, get writers, get people who are very good at imagining things. And the companies do that a lot—they bring writers in.

But the humanistic insights I’m talking about are not just creative and fictional. They’re also understanding history and what you’re building on. The idea of robot: that was a word for a feudal worker. Do we really want to be part of this history? When you actually learn where in the history you are coming in, it changes things.

And then philosophy. I think conceptual work has been extremely fruitful so that you say, ‘OK, you’re building a being. Let’s not go with the being. Let’s go with a different concept.’

What does language now mean when you have machines using it as well? What does that mean for creativity, for autonomy, for the community? For all of these other concepts that are related? I think this kind of work is very productive, but it’s obviously slow. It’s not something that can’t be translated into deliverables just like that.

That’s why academics should really be included as well [as industry]. We have a kind of different approach we can bring.

It does seem like so much of the funding for AI research is coming from industry these days. Is that something you think about much—how the tech industry is shaping research in this field and what this means for the questions we’re asking?

In academia, we offer a counterpoint to the industry. They need to build successful models for the market fast. Our projects are very deep. Deep knowledge that has no space in the industry. It’s basically what they want to eliminate. So we have the means to build our own models—that’s what we’re doing with generative, adversarial networks [editor’s note: the generative adversarial networks Begus refers are a different architecture from the transformers underpinning LLMs. They can learn from raw speech and smaller datasets, in a manner more similar to how human babies pick up language].

So there are better ways to do AI, to create a better future for AI, and I think there are a bunch of good initiatives coming out of non-profits. The Public Interest Corpus, building on the libraries we have. Building models for the public good, the way libraries are for the public good.

Credit: Nina Begus

And I think people will find alternatives to this marketable, generative, general use. It’s so succumbed to this one form—what the industry has. And there are so many other options for how to do this. We’re going to publish our models very soon. The MIT press is supporting the cost. Then the models can be used both by researchers and the general public. We’ve created the kind of interface that anyone not familiar with engineering will be able to use.

What are the key features of those models?

They are closer to how humans learn, because they have two networks: the discriminator and the generator. I call them Higgins and Eliza.

Higgins, the discriminator, says OK, when the generator produces something—and it starts with complete noise—once the discriminator cannot understand the difference between fake data and real data it means the generator learned how to produce fake data to the level of real data. This is how they learn. They start with nothing.

And so we work with them on speech. And what’s interesting: they’re very imaginative, these models. They only got 8 words at the beginning. And started producing new English words, and even started concatenating—creating syntax—all on their own. “Blue car.”

We’re really struggling with just mere vocabulary. We don’t have the words to describe this new reality quite yet.

What’s good about these models: you can peek into the layers inside and see what’s going on. You can even compare them to human brains and look at the neural nets, the way they respond to sound. And it’s very similar.

So in many ways, they are more humanlike than transformers which are so humongous, they are becoming very non-humanlike. Nobody learns language in this way. Whereas with speech, we start with nothing and slowly build up.

So that’s why I think those models are interesting. The resemblance of what’s happening in biological networks is much closer and fun to look at from a research perspective. There’s a lot of research experiments you can’t do on humans but you can do it on visual neural networks.

Do you think we will ever get to the point of having AI that has a sense of self, or consciousness? I feel like that is another trope we’ve pulled from science fiction—that the ultimate end state is an artificial being that has its own sense of personhood.

We all succumb to this idea that the machine speaking back to us has some kind of sentience. It’s easy to make fun of, but we’re all Blake Lemoine a little bit. [Editor’s note: Google engineer Blake Lemoine was put on leave in 2022 after claiming that one of the company’s AI models was sentient.] And there are some people who make the claim that by generating what you need to hear, understanding your inclination, it already has a theory of mind. It’s trying to understand what you need and think. But that’s a very minimal [view].

It really goes back to how you think about intelligence. Some people think, well AGI is already here. [Editor’s note: AGI, or artificial general intelligence, is a term often used to refer to machines that have achieved human-like intelligence.] But I think transformers are just one of the many possibilities. There are many other interesting architectures that will be very different. What you need is a really good benchmark of what cognition is.

I think what’s happening is we’re being challenged from all directions. Language was this last thing that was supposedly only human, or storytelling. Now we’re learning that animals [have language] as well. That was kind of a taboo research topic for a long time, for philosophical reasons. I think one philosophical solution to this problem in machines is: you can have machinic creativity, you can have natural or biological creativity, you can have human creativity. It’s a series of different creativities.

I think this is a better solution than to say: is this conscious, or is this autonomous? When you look at the history of consciousness, it’s a concept that John Locke invented in the 17th century, building on Descartes. Saying only humans have consciousness. So I think we’re just going to have to come up with new concepts.

Another job for the artificial humanities?

I guess so!

How can you help build a better future for AI—and for humans in a world filled with intelligent, creative machines?

Volunteer with AI for Good to join researchers, professionals, and students working to design AI that solves global problems, ethically: https://www.whatcanido.earth/action/ai-for-good/

Volunteer with Tech Shift, a network of student organizations working toward a more just technological future: https://www.whatcanido.earth/action/tech-shift/

Learn from the Ethical AI Network, which has put out principles for responsible machine learning and AI development, and LawZero, which is focused on steering humanity away from dangerous AI applications.

Donate to Data & Society, a nonprofit research group studying the social implications of AI: https://www.whatcanido.earth/action/data-and-society/

Learn from Women in AI Ethics, who’ve offered free classes on AI at public libraries and monthly AI reading circles: https://www.whatcanido.earth/action/women-in-ai-ethics/

Get creative. If we ever want to move past sexy chatbots and sycophantic voice assistants, we need new stories about AI that break us free of the centuries-old Pygmalion narrative template. Been sitting on an idea about a soil-based superintelligence that mimics the fungal mycelial network? Write it down!

By Maddie Stone

Maddie is a prolific science journalist. She is the former science editor of Gizmodo, founding editor of Earther, and runs The Science of Fiction blog, which explores the real world science behind your favorite fictional monsters, alien planets, galaxies far far away, and more.

💌 Loved this issue of The Science of Fiction?

Check out what else we make (or take it easy on the emails, we get it) right in your Subscriber Preferences.

🤝 Thanks for reading. Here’s how we can help you directly:

☎️ Work with Quinn 1:1 (slots are extremely limited) - book time to talk climate strategy, investing, or anything else.

🎯 Sponsor the newsletter - reach {{active_subscriber_count}} (and counting) sustainably-minded consumers.