Welcome back.

We’re almost a week post-daylight savings, the days are getting shorter, and I’m spending longer and longer every morning in front of my Happy Lamp. It’s the perfect time to explore our relationship to the seasons, to rest, and to work.

This week, guest writer Syris Valentine dives into why our circadian rhythms are at odds with our economy, and what beavers, vervet monkeys, and deciduous trees can teach us about honoring winter’s rhythms instead of fighting them.

While other species prepare for rest and social bonding, we keep plugging away at the same 9-5 schedule whether it’s June or January.

Turns out our bodies didn’t get the memo that we’re supposed to ignore the seasons, and artificial lighting just isn’t cutting it.

Let’s go.

— Willow

You’re here because you give a shit.

Every week, we help {{active_subscriber_count}}+ humans understand and unfuck the rapidly changing world around us. Join us (or else).

Life According to the Seasons

By Syris Valentine

Syris is a writer and journalist focused on climate change, social justice, and the just transition. Their work has appeared in The Atlantic, Grist, High Country News, Scientific American, and elsewhere.

If you find yourself struggling to get out of bed and yearning to sleep in as the winter solstice approaches, darkness lengthens, and daylight gets squeezed; it’s not in your head.

It’s in your body. No matter what the clock says when the alarm sounds, if long hours remain before sunrays begin to dye the horizon, the body will resist waking.

Humans are, after all, seasonal creatures.

A study published earlier this year showed that the body's rhythms shift with the seasons, and as they do so, it becomes harder and harder to adjust to work schedules — especially when shifts occur at odd hours. The impact goes beyond a bit of pre-coffee grogginess. The researchers looked at how the circadian clocks of 800 first-year medical interns were affected when they started the shift work common among physicians-in-training. The results showed that when an intern worked a shift misaligned with their circadian rhythm, they reported more symptoms of depression.

The impact was even more pronounced in winter. But, regardless the season, the effect is so significant and has been identified so frequently that the authors noted, “circadian disruption is increasingly being considered a risk factor for suicide.”

Despite these risks, thanks to the lights and heaters and other indoor accoutrements that free us from adhering to slippery solar time, most people follow schedules misaligned to the cycles of Earth and body.

But give the body a chance to adjust and, in short order, it will rest and rise with the sun.

One July, physiologists in Colorado studied the sleep habits of eight adults over a period of two weeks. In the first week, they went about their lives as normal: working, eating, socializing, and sleeping according to their standard habits, exposed the whole while to whatever artificial lights came along with those activities. In the second week, the participants spent a week camping in the Rocky Mountains, and though everyone was still permitted to follow their own schedule and divert themselves as desired, they couldn’t use flashlights or personal electronics; aside from sun, moon, and stars, camp fires were the only source of light.

By the end of the second week, the circadian rhythms for all the participants – even for the self-identified night owls – had shifted two hours earlier on average, with their bodies increasing melatonin production just after sunset and decreasing it before they’d even woken up. Under artificial lighting, however, melatonin typically didn’t subside until they’d already been awake for two hours.

That delay is true for most people, which is why many often feel sleepy well into the morning.

While this particular study didn’t extend beyond the summer, others have investigated sleep changes over the course of the year. Unsurprisingly, people slept longer in winter.

In one small study in the US, the effect was small but notable: a quarter of an hour. A much larger study in Japan found a more pronounced effect: 40 minutes. Still, these are two heavily industrialized countries with hardcore work cultures and all the electric comforts engineering can offer, which may interfere with what the body aims to accomplish. The pre-industrial San people of southern Africa, for instance, tend to sleep for an additional hour when nights are longest and day shortest.

One of the main obstacles to getting extra sleep during the long dark comes from a cultural commitment to endless economic activity.

9-to-5s know no seasons.

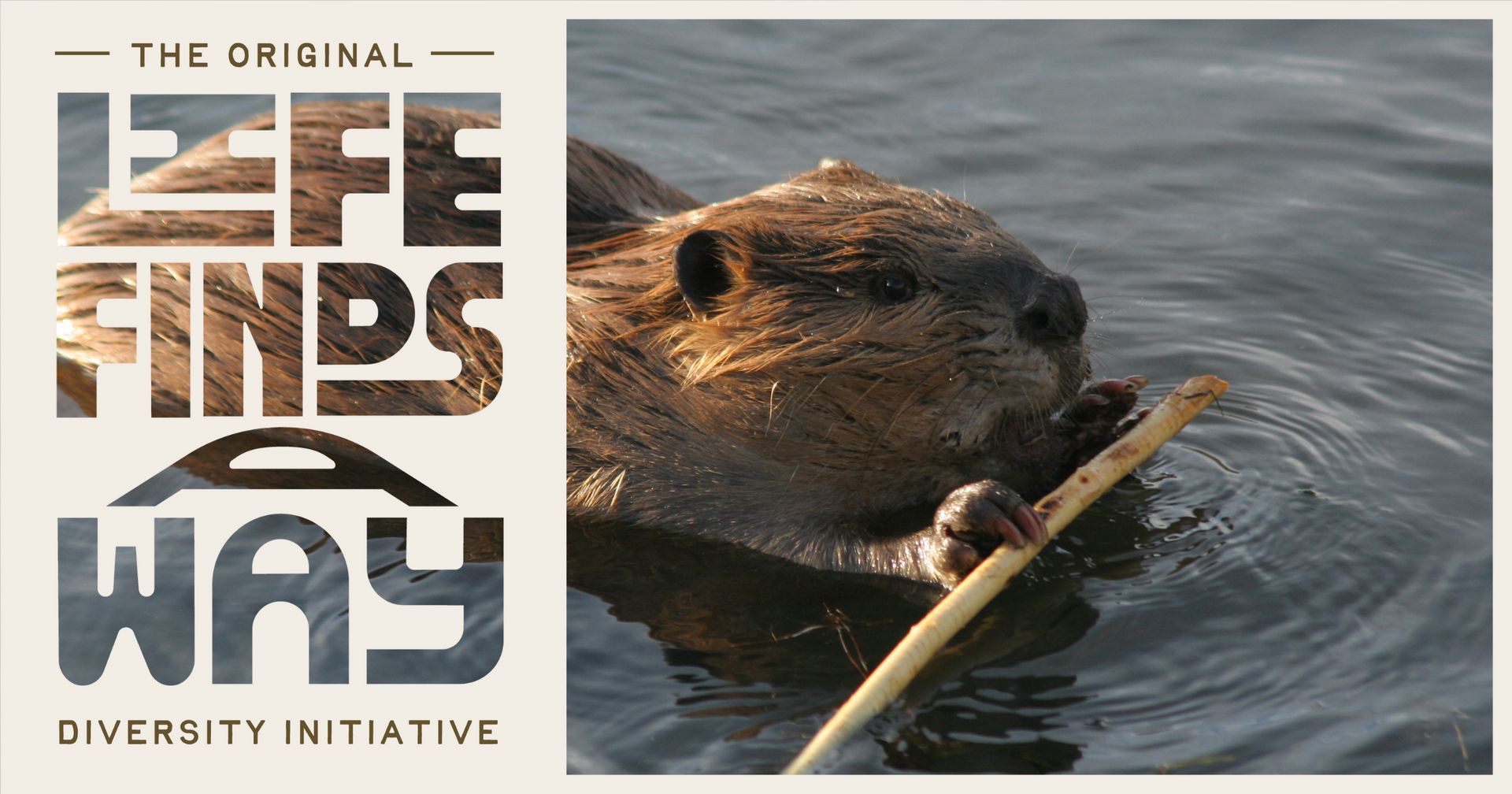

At times, our approach to the economy feels almost inevitable and all but inescapable, yet there is nothing innately human or natural about it. Ecology reveals such. This time of year, trees shed leaves; beavers cache food; bears pack on pounds to hibernate; migratory birds flee to warmer climes. In the industrialized world, however, we continue to plug along day by day according to the same schedule we follow the rest of the year, daring to defy nature’s rhythms even as our bodies clamor for us to slow down, get cozy, sleep in.

If we learned how to adapt our lifestyles, cultures, and economics to shift according to the seasons – in particular to allow for a winter slowdown, or outright stoppage – we’d all be happier for it.

What would it look like to return to life according to the seasons, particularly in the winter when the rest of the world is at its most languid? To answer that question, we can look to beavers, monkeys, and the secret life of trees.

Join the Important Membership to read the rest.

Members get access to every issue of Life Finds A Way -- and everything else we make, too.

Start Your 30 Day Free TrialBenefits include:

- Your choice of our critically-acclaimed newsletters, essays, and podcasts

- A welcome sticker pack!

- Ad-free everything

- Your WCID profile: Track and favorite your actions while you connect with other Shit Givers

- Vibe Check: Our news homepage, curated daily just for you. Never doomscroll again

- Lifetime thanks for directly supporting our work